<<Read Time: 6.5 Minutes>>

Established in 1867, Cheyenne boasts a colorful and storied past...

Local tour guides in Cheyenne, Wyoming often lead visitors on a journey back in time to the Wild West, pointing out significant locations of saloon brawls, old brothels, and notorious interrogation rooms. This "Hell on Wheels" town, brimming with vitality and energy, once held the title of the richest city in the world per capita.

Early adoption of telephones and electricity, accomplishments of legislators and cattle barons, and the victory of women’s suffrage and equal rights often dominate the historical narrative in this corner of Wyoming.

But Cheyenne’s past is intricately entwined with the history of the tribes who called this land home long before Union Pacific laid rails across the plains. Subtle nods to this darker past can be found - driving around Cheyenne today, signs for the Sand Creek Massacre Trail pique visitors’ curiosity, but few ever hear the story of why the signs are here, 250 miles from the National Historic Site in Eads, Colorado.

View of 16th Street, Cheyenne, Wyoming, 1868

What is the Sand Creek Massacre?

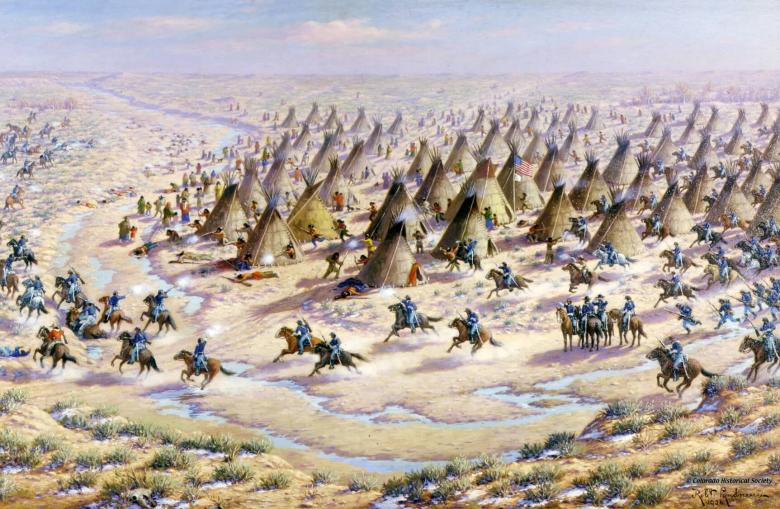

"The Sand Creek Massacre" by Robert Lindneaux portrays his concept of the assault on the peaceful Cheyenne and Arapaho village by the U.S. Army. Courtesy National Park Service.

In the history of the American expansion westward, there was a constant back-and-forth exchange of tragedy between American settlers and Indigenous tribes. The Sand Creek Massacre stands out amongst them as one of the most violent and controversial massacres in the conflict’s history.

In November of 1864, a contingent of soldiers from the 1st Colorado Infantry Volunteers and the 3rd Regiment of Colorado Cavalry Volunteers opened fire on an encampment of around 750 people of the Arapaho and Cheyenne tribes. The people camping there were known to most, including Colorado’s governor, to be peaceful and under the protection of the American flag.

When the killing stopped, around 250 native people including women, children, and the elderly were dead. The barbarism of that event became known as the Sand Creek Massacre, and what happened will forever go down in history as one of history’s most tragic events.

The Sand Creek Massacre: What Happened

For eight hours the 1st Colorado Infantry Regiment of Volunteers and 3rd Regiment of Colorado Cavalry Volunteers battled with the besieged encampment. While the native people were armed, and more than a dozen US military members were killed, the majority of casualties belonged to the Native Americans at Sand Creek.

Around 230 Cheyenne and Arapaho people were killed, most of them women, children and the elderly. After the Battle of Sand Creek on November 29th, members of the American military force continued to mutilate the dead and torture the living. Later testimonies in Congress would reveal the utter carnage and cruelty displayed by the American volunteers.

To tell the whole story of what happened at Sand Creek, we must look back at the years of conflict, the events, and the people leading up to this dark chapter in American History.

1851: Westward Expansion & Increased Conflict with the Arapaho

The adventurous spirit of the American people carried them westward, establishing trade routes and trails across the Great Plains. While the emigrants saw opportunity in front of them, the indigenous peoples of the Plains Tribes had their way of life drastically impacted forever.

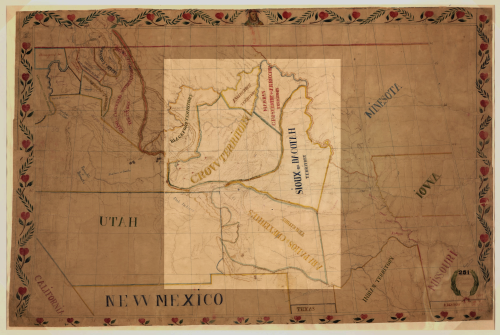

By 1851, a clearer agreement needed to be established with the Cheyenne and Arapaho peoples of the region.

The Fort Laramie Treaty: Divvying up the Land

Jean Pierre De Smet's map depicting the tribal lands set apart in the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851. Cheyenne Arapaho land is the southern portion.

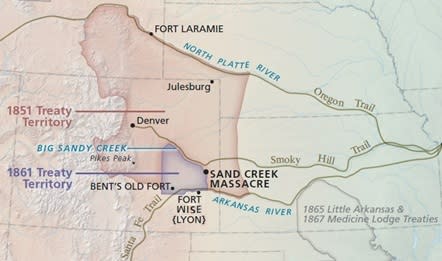

US peace commissioners and representatives of the Plains Tribes met together at Fort Laramie (northeast of modern day Cheyenne, Wyoming) and wrote the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty, recognizing the lands of the tribal people roughly between the Oregon Trail (North Platte River) and the Santa Fe Trail (Arkansas River), a vast 44-million-acre area. The U.S. Army also agreed to designate travel routes for new emigrants, provide supplies and protection to the native peoples.

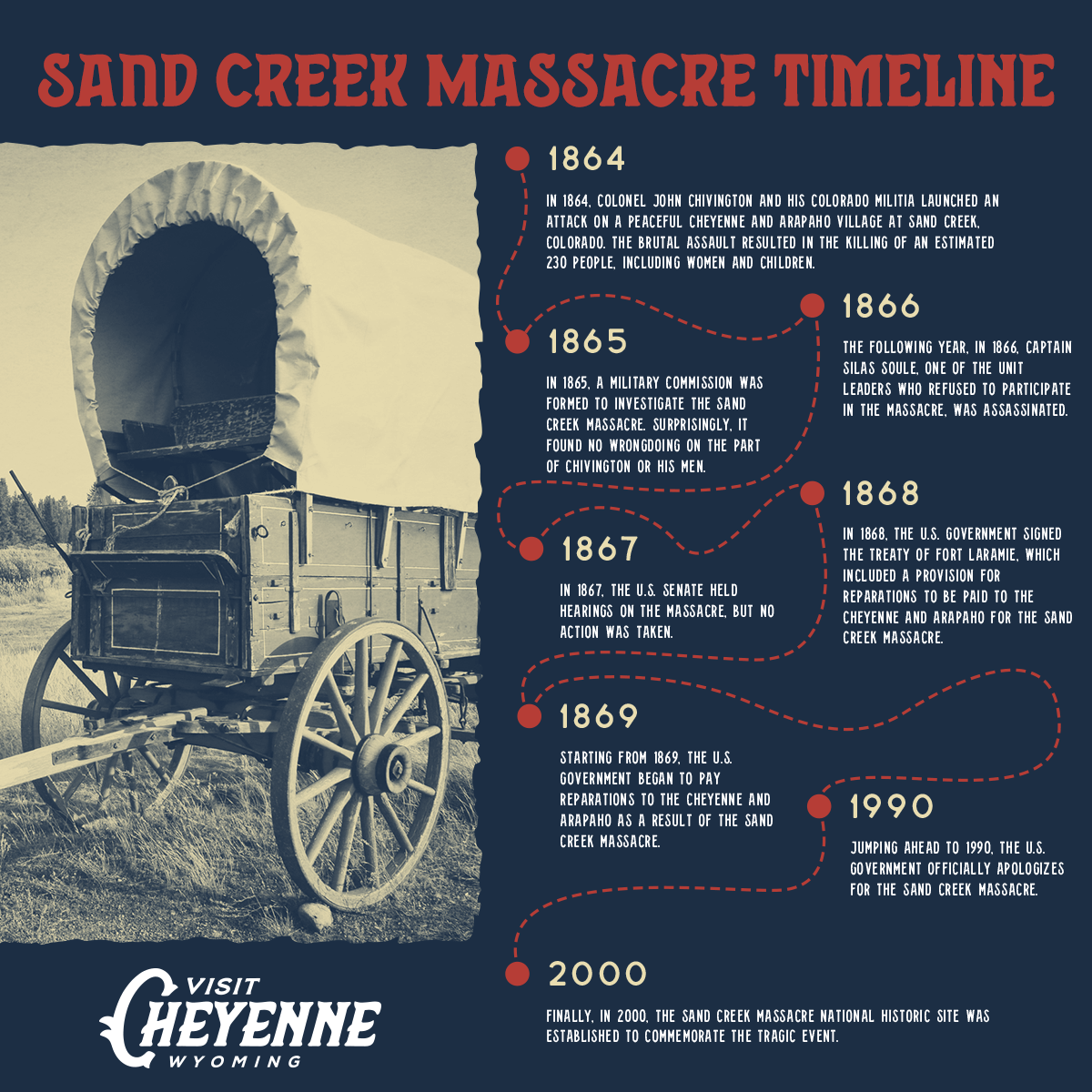

1861: Discovery of Gold Prompts the Fort Wise Treaty

By the end of the 1850s, word got out that gold had been found near Pikes Peak, Colorado. Tens of thousands of new Americans emigrated to the area, many illegally homesteading and building settlements on the tribal land. Residents petitioned for a revisal of the 1851 treaty to favor mining claims. Negotiations began once again in 1860 with only a small minority of tribal leaders represented. As a result the Fort Laramie Treaty is regarded by many to be a broken promise by the U.S. Government to native tribes.

Who signed the Fort Wise Treaty of 1861?

Federally-recognized Cheyenne and Arapaho lands from 1851-1861. National Park Service map in Sand Creek Massacre NHS brochure.

The Fort Wise Treaty was signed in 1861 by a mere handful of chiefs (the majority of chiefs refusing to sign the document). The tribal land allotment was reduced by over 90% - cut down to only 4-million-acres, between the Smoky Hill Trail (Big Sandy Creek) and the Santa Fe Train (Arkansas River). (See Map.)

Meanwhile, the country’s attention turned eastward to the growing war between the Union and Confederacy, but the new Territory of Colorado faced local conflict by peoples who did not recognize the treaty.

Tensions rose as promised supplies got rerouted to the Civil War, the Homestead Act allowed the sale of plots of former tribal land, and President Lincoln declared the federal right of way for land to establish the railroad and telegraph, superseding any previous or future treaty land agreements.

In 1864, there were four unprovoked attacks by the U.S. military on Cheyenne villages and back and forth retaliation between the two sides began.

1864: Causes & Consequences of the Indian War

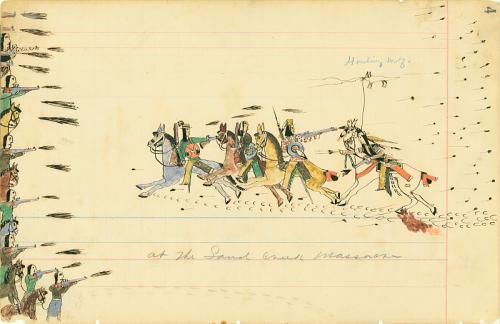

An eye-witness ledger drawing by Howling Wolf, circa 1874-1875; Depicting the Sand Creek Massacre in Eads, Colorado.

The Indian War of 1864 resulted in downed telegraph lines, stolen cattle, raided mail and freight wagons, and reported attacks on farms and stage stations.

The 1st Regiment Colorado Volunteer Cavalry attacked a Cheyenne village in Kansas, killing peace ambassador Chief Lean Bear who wore the medal given to him by President Lincoln just a year earlier.

An American family outside of Denver was found murdered and mutilated, triggering panic in the city. The territorial government’s strategy began to change.

While offering to relocate “Friendly Indians,” Governor John Evans gave the order (with authority from the U.S. War Department) to eliminate hostile natives - “pursue, kill and destroy all hostile Indians that infest the Plains.”

Within a month, people from both sides of the issue called for peace and hostages were exchanged. Over the following weeks, 750 Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes people gathered at Sand Creek for deliberations with the U.S. representatives.

The Battle of Sand Creek

Hide painting by Stone Rabbit, depicting the the U.S. military attacking a peaceful Chief Black Kettle at the Sand Creek Massacre near Eads, Colorado. Original artwork on display at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming.

On the morning of November 29, 1864, Colonel Chivington commanded his 675 troops to attack the village, despite the American and white flags flying above the camp as instructed.

Captain Silas Soule and Lieutenant Joseph Cramer refused to command their men to join, but the remaining soldiers quickly dissolved into chaos and slaughtered an estimated 230 natives, many of them elderly and up to 150 of them women and children.

The accounts of what happened at the Battle of Sand Creek speak of mutilation, scalping, and torture. The elderly to the unborn lay chopped up in pieces, scattered across the fields.

The survivors fled to a camp of Cheyenne to the north, with the soldiers shooting artillery at them, regardless of age or ability to defend themselves. Only about a dozen U.S. soldiers were killed that day.

The Aftermath of the Sand Creek Massacre

Soule and Cramer, the men who refused Chivington’s orders, wrote letters to their commanding officer concerning their accounts of the Battle of Sand Creek. Their letters circulated among military leaders and politicians.

Portrait of Captain Silas Soule, one of two unit leaders who refused to participate in the Sand Creek Massacre. Soule brought to light the war crimes and triggered three investigations. Several months later, he was assassinated for speaking out. His murderers were never brought to justice.

Official Investigation and Removal of Governor and Colonel

In the end, an official investigation was launched and eventually word got out publicly about the truth of the massacre. Within nine months, the territorial governor John Evans and Colonel Chivington were each removed from their positions for their roles in the slaughter. Chivington, with his term of service soon ending, resigned from the Army, escaping a court-martial for the massacre. Chivington, with his term of service soon ending, resigned from the Army, escaping a court-martial for the massacre.

National Outrage and Local Complications

The media reflected national outrage on behalf of the Native Americans, but the locals had a continued complicated relationship.

Continuing Conflict and Consequences

Captain Silas Soule was one of two unit leaders who refused to participate in the Sand Creek Massacre. Soule brought to light the war crimes and triggered three investigations. Several months later, he was assassinated for speaking out. His murderers were never brought to justice.

The West faced years of conflict between the tribespeople and the Americans with many more battles, massacres, and relocations.

Eventually, all natives were forced to assimilate to white society or removed from Colorado and sent to reservations in Kansas, Montana, and Wyoming.

The Sand Creek Massacre Trail: Present Day

Modern day Sand Creek Massacre location, near Eads, Colorado.

Today, the state-designated Sand Creek Massacre Trail in Wyoming passes through Cheyenne, Laramie, Casper, and Riverton, north to Ethete in Fremont County on the reservation. The path represents journey of the Cheyenne and Arapaho peoples in the years following massacre, covering 600 miles.

Spiritual Healing Run

An annual Spiritual Healing Run is held for the descended youth of the Arapaho and Cheyenne tribes, running the length of the trail over several days to remember and honor their past, to bring healing to their community.

Impact of the Massacre and Recognition

The city of Cheyenne was founded two and a half years after that terrible day in history, but no doubt the arrival of the Wild West had an enormous impact on the tribal nations. The Sand Creek Massacre Trail serves as recognition of the change our progress and adventure created. The Native Americans have had a difficult road – we are honored to acknowledge their journey and lift them up in any way we can.